Recently on social media, I witnessed a lot of discussion regarding the rotator cuff and all the misconceptions people have about it. The rotator cuff appears to be one of the most misunderstood physiological structures I have encountered. If you have not taken an anatomy course, or perhaps multiple, then it is hard to get a good handle on any anatomy, much less the rotator cuff. Social media does not help much either. There is a ton of wrong or misguided information that is made visible to millions. This article is meant to serve as a brief anatomy lesson about the rotator cuff and its components in hopes that you will gain a better understanding of what it is and what it is responsible for.

What is the rotator cuff?

Some believe it to be a single structure that surrounds the shoulder joint. When you hear someone say “I tore my rotator cuff” it sounds as though they tore just one structure. The rotator cuff is actually a group of four muscles. These four muscles are collectively referred to as the rotator cuff because they assist the shoulder with external or internal rotation. However, their most important role is to help to stabilize the shoulder joint. This is known as the glenohumeral joint, during movements of the arm.

The muscles of the rotator cuff

I will be brief in this breakdown of these muscles. Note that origin refers to where a muscle starts. And insertion refers to where the muscle ends, or where it attaches.

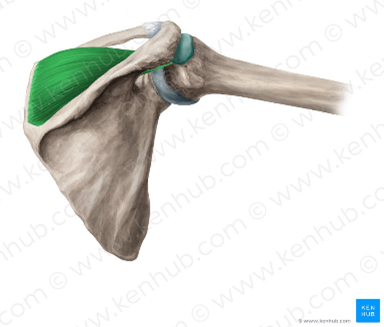

- Supraspinatus

- Origin and insertion: Originates on the top of the scapula (shoulder blade) and attaches to the humeral head on what is called the greater tubercle.

- Action(s): Externally rotates the arm; Abducts the arm (raises laterally or to the side, away from the body) about 15 degrees. Assists the deltoid with abduction to 90 degrees.

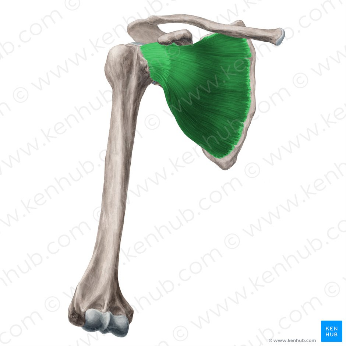

- Infraspinatus

- Origin and insertion: Originates on the posterior, or back side, of the scapula in a location known as the infraspinous fossa and attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- Action: Externally rotates the arm.

- Subscapularis

- Origin and insertion: Originates on the anterior, or front, of the scapula in a location known as the subscupalar fossa and attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

- Action: internally rotates the arm

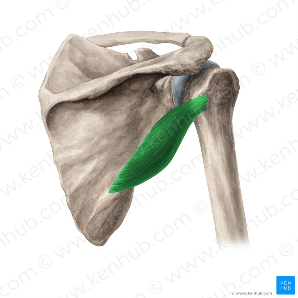

- Teres Minor

- Origin and insertion: Originates posteriorly on the scapula, close to the scapula’s lateral border, and inserts on the greater tubercle of the humeral head.

- Action: Externally rotates the humerus.

It is important to know the location of muscles, as that helps to understand that particularly anatomical area as well as to know and understand their function. Muscles always pull towards their origin. Looking at the descriptions of the rotator cuff muscles, and viewing the images, we can see that the muscles begin (origin) on the shoulder blade, cross over the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) and attach (insertion) on to the humerus and effectively pull the humerual head into the glenohumeral joint. And thus, we get STABILIZATION! The body is amazing, right?

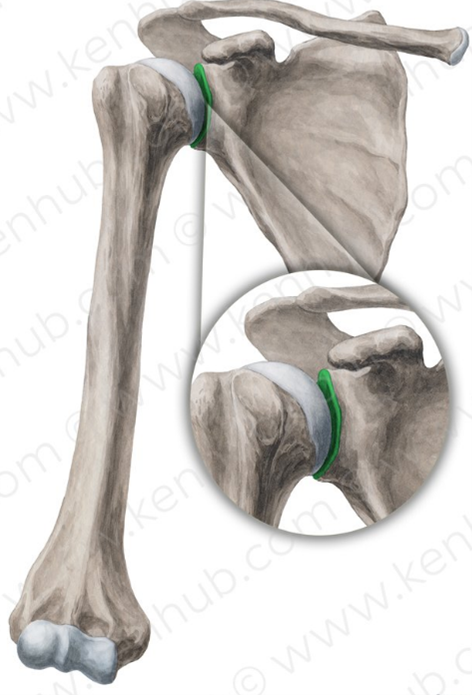

The glenohumeral joint

The structure of the glenohumeral joint demonstrates why stabilization that the rotator cuff muscles provide is so necessary. The humeral head is essentially just the endpoint of the humerus that is shaped like a ball. This ball faces inward, towards your body, and sits within the glenoid fossa of the scapula. The glenoid fossa is cup-shaped, which is perfect for that ball I just told you about. So, interaction with the humeral head and glenoid fossa forms the glenohumeral joint. But here is the kicker: the humeral head is quite large in comparison to the shallow glenoid fossa. If you like numbers, the ratio of humeral head size to glenoid fossa size is 4:1. SUBSTANTIAL DIFFERENCE! But it is that size difference that makes the shoulder so unique because it allows so much movement!

Extra mobility in our shoulder is great because it allows us to reach high to get a cookie from the cookie jar, scratch the middle part of our back without needing a wall, or to reach back in the car in that awkward angle to put the pacifier back in our baby’s mouth during a long trip. Having this much freedom of movement is awesome right? Well yes, but that increased mobility and freedom at the glenohumeral joint is the reason why you see so many shoulder injuries, including dislocations.

This, again, demonstrates the importance of our rotator cuffs.

To reiterate, the 4 muscles that comprise the rotator cuff reach across the shoulder joint from their origin on the scapula, grab onto the humerus and pull it towards the scapula and into the glenoid fossa. Movements of the entire arm represent a dynamic relationship between the muscles, ligaments, and bones. The rotator cuff muscles, as well as other muscles not discussed, are active in some way during all arm and shoulder movements. They are either creating force, assisting larger muscles with movement, or providing stabilization to the joint.

Applying this information

You might be wondering why I even wrote this article and how it applies to you. I believe everyone should know some anatomy! Whether it is personal training or physical therapy, I provide education so that my patient or client can have a better understanding of themselves. Knowing more about your own anatomy can help you understand why/how an injury occurred, what specific movements can help or hurt your recovery, and how to train yourself more efficiently. If you train but know what the movements are doing or are for, you most likely will not be maximizing it and your training!

What I need you to realize about your rotator cuffs is that they are small and relatively weak in comparison to the main movers of the shoulder such as the deltoids. This means that your approach to training them should be a little different. Also, the health of your shoulder is very dependent on position and muscular position. Extreme postures, such as slouched or rounded shoulders, effectively overwork some muscles while stretching and/or weakening others, while also misaligning the bones and joints. This misalignment can lead to impingement of certain muscles or structures, cause trauma via rubbing, and cause inefficient or incorrect use of muscles. I will not harp on posture much, but just know that being in one posture for extended periods, especially an extreme posture, can cause negative effects later.

Whether you are recovering from an injury or just want to strengthen your shoulders, you must not only give attention to the rotator cuff muscles but also the other muscles of your shoulders and back. This includes the traps, lats, deltoids, rhomboids, and many others that play a major role with strength and stabilization.

General training recommendations for the rotator cuff muscles:

- Always establish and maintain a good posture.

- Shoulders down and pulled back, head and neck in neutral alignment.

- Utilize resistance bands or cable machines with very light resistance.

- Free weights are fine if you have no other option, but bands and cables are most effective in isolating the rotator cuff muscles.

- Perform the actions of the muscles = internal and external rotation

- You will commonly see these performed with the arm/elbow pinned to a person’s side.

- Perform high reps = 12-20

- The rotator cuff muscles are mainly stabilizers, and as such, they require a little more muscular endurance.

- Perform these exercises as a warm-up, especially on training days that incorporate upper body pushes.

- Regularly exercise your back muscles! Pull, pull, pull!

I hope this article is educational and helps you to understand the shoulder anatomy better. Although it does include some recommendations for training, its main purpose was to be a simple anatomy lesson. If you would like to know more about your shoulder, have questions regarding training or rehabbing your shoulder, please don’t hesitate to reach out!